In other posts, I’ve mentioned what we call the “grid rules” but haven’t gone into detail about them. We call them “grid rules” because the actual regulation is laid out in a grid chart, but the formal name is the “Medical Vocational Guidelines.” The citation to the regulation is complicated: It’s Appendix 2 to Subpart P of Part 404. Here’s a web link: https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/cfr20/404/404-app-p02.htm

If you just go to that page and scroll through, you may find it somewhat confusing. Let me shed some light on it.

First, a broad overview of the law. When a person attains age 50, they are categorized as a “person closely approaching advanced age.” At this age, a person can be found disabled if their functional capacity is only enough for “sedentary” work, which is specifically defined, but basically no heavy lifting or prolonged standing and walking. If you are that limited after age 50 and don’t have past work that can still be done with your limitations, and can’t easily pick up other sedentary work using skills from your past work, you are disabled. That’s really all there is to it. At age 55, the standard changes again, and if you are limited to “light” work, which is basically just no lifting and carrying over 20 pounds, and you’ve only done heavier physical work before, you can then be found disabled.

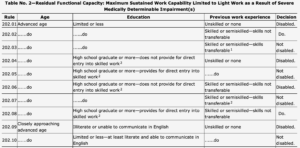

There’s a little more nuance to the rules, but not that much. The grid divides people by age, education level, and the skill level of their past work, and the considers whether they have transferable skills to that exertion level. There’s a specific rule for each, and each rule has a number, but the rules kind of break down in categories. Everyone below the relevant age category will be found “not disabled” under the grids. You may notice that there is one further subdivision for people aged 45 to 49, which is illiteracy; in this rare exception, people can apply the grid rules below age 50. If you are reading this page, this rule will not apply to you, but it may apply to a friend or family member.

Once you are in an age category where the grid rule can direct a “disabled” finding, we then need to look at education level, but this actually makes relatively little difference. Education level will only direct a “not disabled” finding if the individual has education that provides a direct path to skilled work, such as a professional degree or certificate, but only if that degree is relatively recent.

Next is work history. The basic division isn’t just skilled versus unskilled; only “skilled with transferable skills” directs “not disabled”, while “unskilled,” “none,” and “skilled without transferable skills” all direct “Disabled.”

The last column in the grid is just the conclusion – the words “Disabled” and “?Not disabled.” “Do.” in the chart means “ditto” or “same as above. Why they took that shortcut, nobody knows.

There are three tables in the grid rules. Table 1 is the set of rules for individuals limited to “sedentary” work. The rules that most often get applied here are 201.09, 201.12, and 201.14. Table 2 is for individuals limited to “light” work. The winning rules here are 202.01, 202.02, 202.04, 202.06, and 202.09. These rules have in common the absence of transferable skills.

So what are transferable skills, and why do they matter? The stated premise behind the grid rules is that it’s harder for older people to adapt to new kinds of work than it is for younger people. The idea is that if you’ve only done physical work for your whole life, adjusting to intellectual or clerical work at an older age is too difficult, especially considering the unspoken discrimination against older job applicants. The split again at age 55 is based on the idea that someone who’s only done heavier work is less likely to find work that is easier without a radical change that can’t be easily accomplished.

That’s why transferable skills matter: if you already have skills that apply directly to less physical work, then that whole idea of an adverse job market doesn’t really apply to you, because, at least this is the theory that the government relies on, you should be able to just walk into a job based on your skills and get right to work without any trouble.

There are narrow rules for applying this transferable skills rule. First, it can only be applied from “skilled” or “semi-skilled” jobs – if your past work was considered unskilled labor, you cannot have transferable skills. But if you were a skilled worker, essentially in any job that required specific education or training beyond someone showing or telling you what to do, you could have acquired skills that can be applied to other work. The government is responsible for identifying the specific skills that you have from past work, and identifying specific jobs that those skills enable you to do. The jobs generally have to require very minimal adjustment, and have to be considered to be in the same industry. This is another reason to have a skilled advocate at your hearing, to make sure that this rule is not applied improperly.

We have dealt with improper application of the grid rule, particularly improper application of the transferable skills portion of the rule, in hearings and in appeals. When I am in a hearing, a large part of my job is to question and cross-examine vocational experts about the presence or absence of transferable skills, and make sure that if they identify skills, they are valid and appropriate. And if despite my efforts a vocational expert provides inaccurate testimony, and the judge relies on it, that is something we have experience fighting in the higher appeals, especially Federal District Court.

The grid rules are often very helpful in helping older claimants access their Social Security benefits. Make sure you have a skilled advocate to make sure the rules are applied correctly.